Orofacial granulomatosis (OFG) describes the presence of granulomatous inflammation of the face and lips. It can also affect features inside the oral cavity such as the gums, tongue and base of the mouth. OFG is quite a rare condition, with incidence rates not well known. It affects children and adults; people are more commonly diagnosed in their 20s. The highest number of cases has been reported in Scotland, United Kingdom. Despite effective treatments available, relapse is not uncommon. OFG is closely linked with Crohn’s disease, a type of inflammatory bowel disease, and it has been reported that approximately 25% of patients with OFG also present with Crohn’s disease1.

What is orofacial granulomatosis?

What are the key symptoms of OFG?

Symptoms can include swelling, ulcerations, tags and nodules, as well as erythema on the skin around the mouth.

What causes OFG?

No apparent cause of the onset of OFG is outlined in the literature. It is known, however, that the cause is likely to be multifactorial, involving allergic, genetic and maybe even infective components. The oral microbiome may even have a role to play!2

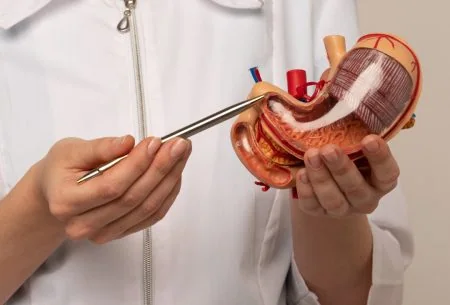

How do you diagnose OFG?

How do you diagnose OFG?

A specialist oral medicine clinician makes the diagnosis using oral examination. The gold standard is taking a biopsy from the affected part of the oral cavity and examining it for the presence of non-caseating granulomas. As taking a biopsy of the lip or mouth can be quite invasive, this may not be used as commonly now as in previous years.

How is OFG treated?

How is OFG treated?

Interestingly, the primary and often first-line treatment for OFG is dietary intervention! This involves a 12-week trial of a strict cinnamon and benzoate-free diet under the supervision of a dietitian. Importantly, due to the restrictive nature of the diet, it should be initiated under the guidance of a specialist oral medicine team with access to a dietitian.

Benzoates can exist naturally and also artificially in manufactured or processed foods. Individuals trialling this intervention will require counselling on ingredient label reading for certain E-numbers and flavourings, and also on the natural benzoates that may be in their habitual intake (for example, tomato puree/tea/chocolate/berries, although this is quite an extensive list).

Ideally, the diet is trialled for a defined period, not long-term. Reintroductions using 4-day food challenges, gradually increasing portion sizes, may help identify triggers and thresholds for certain omitted benzoates. This is likely to improve food enjoyment and also help diversify the diet so the individual does not feel overly restricted.

Some literature also supports a trial of exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN), or a solely liquid diet, for treating OFG in children3. Again, it is crucial that the indication, initiation, and monitoring of such a trial be under the supervision of a specialist dietitian and in a confirmed diagnosis of OFG that has been discussed by the multidisciplinary team. EEN is not always very well accepted or tolerated by young children, and modification to the intake of benzoates is more commonly used in practice.

Where dietary intervention fails, immunosuppression may be utilised, whether topical or systemic. Intralesional steroids, antifungals, antibiotics, and other drugs may also be used as indicated on a case-by-case basis.

Takeaway

OFG is a rare, relapsing inflammatory condition of the mouth that can resemble Crohn’s disease, though many people with OFG will never develop it. Diagnosis should always be made by a specialist oral medicine team, often working alongside gastroenterologists and dietitians. If you’re experiencing persistent oral ulceration or lip swelling, consult your GP about a referral. For those diagnosed, dietary intervention — most commonly a 12-week cinnamon and benzoate-free trial — is the first-line treatment, best supported by a specialist dietitian. They can guide you through the process, help identify food triggers, and support safe reintroductions to avoid unnecessary long-term restrictions. If dietary changes don’t bring relief, further medical management from the oral medicine team may be needed.

This article was authored by Alice Twomey, a gut specialist dietitian. Do you need support with a symptom, condition or goal? You can book an appointment with Alice Twomey or any of our specialist team members here.

References

- Campbell H, Escudier M, Patel P, Nunes C, Elliott TR, Barnard K, et al. Distinguishing orofacial granulomatosis from crohn’s disease: two separate disease entities? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(10):2109-15.

- Goel RM, Prosdocimi EM, Amar A, Omar Y, Escudier MP, Sanderson JD et al. Streptococcus Salivarius: A Potential Salivary Biomarker for Orofacial Granulomatosis and Crohn’s Disease? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;17;25(8):1367-1374.

- Mutalib M, Bezanti K, Elawad M, Kiparissi F. The role of exclusive enteral nutrition in the management of orofacial granulomatosis in children. World J Pediatr. 2016;12(4):421-424